The question of when were scented candles invented is not simple, because the answer depends entirely on definition. Does the history begin with the incidental sweet scent of natural beeswax, or only when fragrance was intentionally added? This definitive, era-by-era timeline tracks that evolution, moving from ancient aromatics to the non-toxic modern choices like soy wax and safe fragrance oils buyers prioritize today. First, we define the true invention threshold.

1. Defining the Modern Scented Candle

To accurately define when were scented candles invented, we must distinguish between two core product categories:

-

Naturally Scented Burnables: Products, like ancient beeswax or herb-infused tallow, where the mild aroma is an incidental byproduct of the material. Primary function: illumination.

-

Intentionally Fragranced Candles: Products where non-native aromatics or oils are added to the wax (paraffin, soy, etc.) explicitly to scent a space. Fragrance, not light, is the core function.

When readers ask about the "invention," they are referring to the second category: the creation of a widely marketed consumer product defined by fragrance delivery.

The history moves through three stages leading to this modern commodity:

-

Ancient World: Aromatics (resins, herbs) were burned alongside wax or fat for ritual or odor masking. The focus remained light output.

-

Pre-Industrial Era: High-cost, intentional infusion became a luxury practice, using expensive natural oils added to beeswax for religious or aristocratic purposes.

-

Industrial Era (19th/20th Century): The invention of cheap, synthetic fragrance oils and mass-produced paraffin wax made intentional scent delivery affordable and accessible, establishing the modern, mass-market category.

This final stage marks the true technical and commercial birth of the scented candle.

2. The Ancient World: Aromatics and Incidental Scent

Illumination was the ancient candle’s core purpose, yet the demand for home fragrances predates effective lighting by millennia. Early lighting relied on animal fat (tallow) or simple oil lamps, which produced strong smoke and foul odors. Since light was the primary goal, scent was often an unpleasant byproduct. This functional limitation required cultures to pursue desired aromas separately through the burning of pure aromatics.

These traditions set the cultural precedent for scented environments across the world:

-

China: Early lighting traditions used insect waxes or animal fats. True fragrance was delivered separately via specialized incense and decorative censers, maintaining a clear distinction between light source and desired scent.

-

India: Ritual use of ghee (clarified butter) and oil lamps provided sacred light. To cleanse the air, sophisticated natural resins and herbs were intentionally burned alongside them, enhancing the spiritual environment.

In the Mediterranean and Middle East, costly resinous woods like frankincense and myrrh were high-status commodities burned in braziers to purify spaces. These ancient methods established a clear, universal demand for pleasant living spaces. This persistent cultural expectation for a desired scent is the foundational economic driver that the modern scented candle would eventually inherit.

3. The Mediterranean Shift: Beeswax, Ritual, and Roman Adaptation

The transition to intentionally scented burnables started in ancient Egypt, driven by the adoption of beeswax. Unlike smoky tallow or oil, beeswax emits a naturally sweet, honeyed aroma, providing the first widespread incidental fragrance in a lighting source. Egyptians also prized aromatics for ritual cleansing, utilizing resins and spices (like the famous Kyphi incense) in temples and during burials. These costly, sophisticated aromatics were intentionally burned for purification, establishing a strong cultural link between fire, purification, and desirable scent.

The Romans then normalized wax burnables for widespread domestic and ceremonial use. Rapidly growing Roman cities faced serious sanitation challenges, making basic odor management a daily necessity. Candles and torches provided practical illumination, but their subtle wax scent also helped mitigate prevailing urban smells. While Romans excelled at personal perfumes (unguents), evidence suggests that the intentional infusion of specific fragrance oils into the wax remained a high-cost, specialized practice rather than a common commodity.

This consistent, practical demand for masking foul environments—from Egyptian ritual to Roman city life—set the stage for change. As Western Europe transitioned from antiquity, the increasing density of early medieval cities made odor control via intentional scenting a critical driver for future innovation in fragrance delivery.

4. Medieval Europe: Tallow, Beeswax, and the Necessity of Odor Control

Life in early Medieval Europe was defined by pervasive, inescapable odor. Increasing population density, poor sanitation, and lack of ventilation forced fragrance usage to shift from an aristocratic ritual to a practical necessity for daily comfort and odor management.

This necessity created a clear, class-based split in lighting materials. Most households relied on cheap tallow (rendered animal fat) for light. Tallow produced heavy smoke, inconsistent burn, and a strong, acrid smell that often intensified the existing environmental odors.

The solution for the affluent was beeswax. Though primarily for illumination, these candles burned cleaner, brighter, and produced a mild, naturally honeyed aroma. Since beeswax was prohibitively expensive, its use—reserved for cathedrals and elite homes—linked clean air directly to affluence.

This dichotomy demonstrates the critical historical driver for intentional scenting by showing the immediate trade-offs:

-

Tallow: Low-cost light, high-odor byproduct.

-

Beeswax: High-cost light, low-odor incidental scent.

To combat density and the stench of poor materials, the wealthy infused beeswax with expensive spices or burned aromatics separately. This pervasive, functional need for odor control is the direct precursor to the modern motivation for purchasing home fragrance.

5. The Renaissance: When Perfumery Became a Status Symbol

During the Renaissance (15th–17th centuries), the candle officially transcended utility to become an integral component of ambient luxury. This shift was fueled by the emergence of professional perfumery and the rapid expansion of international trade.

Merchant fleets imported exotic aromatics—spices, resins, and sophisticated natural fragrance oils—from Asia and the Middle East. Centers of expertise, notably in France (Grasse) and England, quickly flourished, transforming these raw commodities into complex compositions. The wealthy, seeking distinction from the common masses relying on foul-smelling tallow, began using intentionally fragranced beeswax.

This practice normalized the idea that home fragrance was a measurable marker of taste and affluence. Early popular scents—such as lavender, rose, and vanilla—became essential elements of aristocratic relaxation and hosting rituals. These highly desirable scented candles were not masking odors; they actively signaled comfort and social standing.

This period established the lasting consumer psychology that scent equals status. Despite the high demand from the elite, the product remained inaccessible to the public. The biggest acceleration toward the modern form of the scented candle still required a technological breakthrough: the invention of cheap, consistent wax, which arrived with the Industrial Revolution.

6. The Industrial Revolution: Wax Chemistry and Mass Accessibility

The demand for luxurious home fragrance was established by the Renaissance elite, but the category remained stalled by cost and material limitations. The core frustration was chemistry: traditional beeswax was too expensive, and inconsistent tallow was too smoky to carry delicate aromas effectively.

The 19th century resolved this ceiling by industrializing the material supply chain. Technical advancements created the first true ingredients for mass-market scented candles:

-

Wax Consistency: The introduction of Stearin (a hard, clean derivative) and Paraffin wax (distilled from crude oil in the 1850s) revolutionized the base. Paraffin was colorless, odorless, consistent, and dramatically cheaper than natural alternatives.

-

Mass Accessibility: This cost reduction was essential. Candles shifted from a costly emergency necessity to an affordable home decor item for the rapidly growing middle class.

A neutral, reliable wax base provided the perfect substrate for fragrance delivery. Simultaneously, the growth of modern perfumery enabled expansion. Synthetic fragrance chemistry allowed manufacturers to stabilize and standardize powerful aromas at a fraction of the cost of traditional essential oils.

This confluence of cheap, consistent wax plus affordable, diverse synthetic scents broke the aristocratic bottleneck, setting the stage for the category's transformation into the massive consumer product we know today.

7. The Great Pivot: From Utility to Lifestyle Product

Once electricity democratized indoor lighting, the candle's core utility value evaporated, yet its market value exploded. The shift was radical: no longer required for illumination, the candle was repositioned as a dedicated delivery system for home fragrances and an indispensable component of interior decor and relaxation rituals.

The pivot relied on advancements in industrial fragrance chemistry. Modern chemistry, not just paraffin from the Industrial Revolution (Section 6), provided the engine for mass-market variety. Synthetic scents offered stability, cost-effectiveness, and incredible diversity, allowing profiles impossible to extract naturally. This consistency enabled mass-market brands (like Yankee Candle) and luxury players (like Diptyque) to define the modern category.

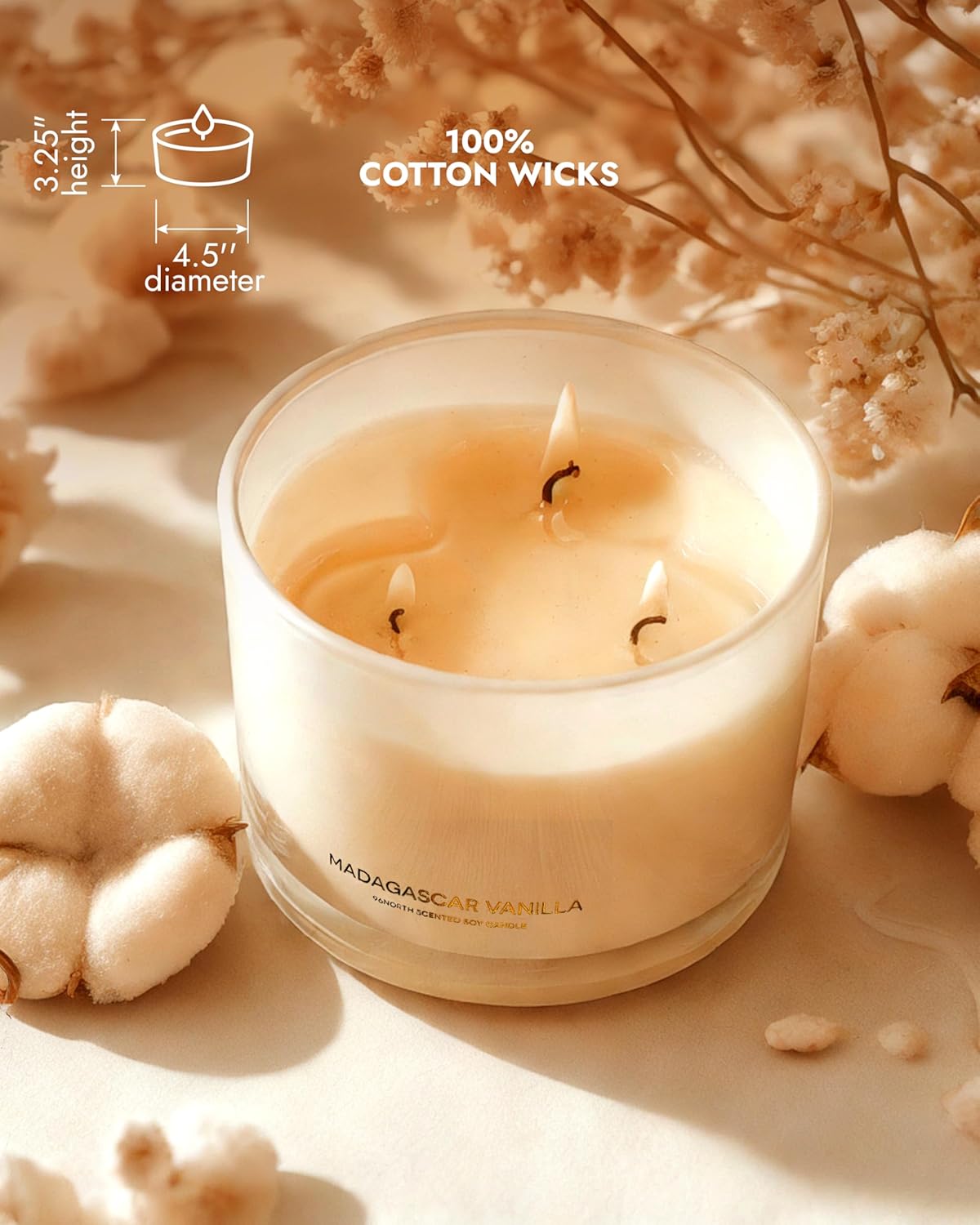

Increased consumer awareness spurred scrutiny over materials. The use of petroleum-derived paraffin wax and certain synthetic oils sparked demand for cleaner alternatives. This led directly to the rise of plant-based waxes. Consumers now overwhelmingly prioritize non-toxic soy wax candles and coconut blends, viewing them as a safer choice that provides a cleaner burn and superior ethos.

For shoppers prioritizing clean materials paired with complex scent profiles, brands like 96NORTH represent this new equilibrium. They blend sophisticated scents with a cleaner base. The candle successfully transformed from a necessity for light into a luxurious ritual for scent delivery.

Frequently Asked Questions About Scented Candles

When were scented candles invented, exactly?

The intentional infusion of fragrance into a wax base for mass consumption occurred during the Industrial Revolution, coinciding with the widespread availability of Paraffin wax and synthetic scents in the mid-19th century. While ancient cultures burned naturally sweet-smelling beeswax (incidental scent) or aromatic resins for purification, the modern product, defined by its function as a scent delivery system, began when chemistry made dedicated fragrance oils affordable for the middle class.

What’s the difference between essential oils and fragrance oils in candles?

Essential oils (EOs) are compounds extracted directly from plants, representing a natural, complex aroma. Fragrance oils (FOs) are synthetic or blended compounds formulated to achieve a stable, consistent scent throw. FOs are highly stable, offer greater scent diversity, and cost significantly less than EOs. High-quality scented candles often use refined fragrance oil blends because they perform reliably, resisting oxidation and maintaining complexity throughout the burn.

Are non-toxic soy wax candles better than paraffin candles?

Consumers typically prioritize non-toxic soy wax candles because they are plant-based, renewable, and often perceived to provide a cleaner burn than petroleum-derived paraffin. Whether they are "better" depends on the overall formulation: high-quality paraffin burns cleanly with proper formulation, while a poorly formulated soy candle may perform poorly. For a superior choice, look for high-grade natural waxes combined with safe, phthalate-free fragrance oils.

Do scented candles actually help with relaxation?

Yes, scented candles can significantly aid in relaxation, though the benefits are two-fold. First, the ritual of lighting the candle and enjoying the ambient light creates a powerful mood cue, transitioning the mind into a relaxed state. Second, specific aromas, particularly lavender and vanilla, trigger measurable psychological responses associated with lowered stress and improved mood, validating the use of home fragrances as a calming tool.

What should I look for when buying a safe scented candle for my home?

Prioritize material transparency and performance elements. A safe, high-performing candle should feature:

- Wax Type: Plant-based waxes (soy, coconut, or beeswax).

- Wick: 100% cotton or wood wicks (avoid metal core wicks, especially lead).

- Fragrance Policy: Explicitly phthalate-free and ideally IFRA-compliant.

By selecting transparent brands focused on modern scent complexity and clean materials—like 96NORTH—you ensure a premium and clean home fragrance experience.